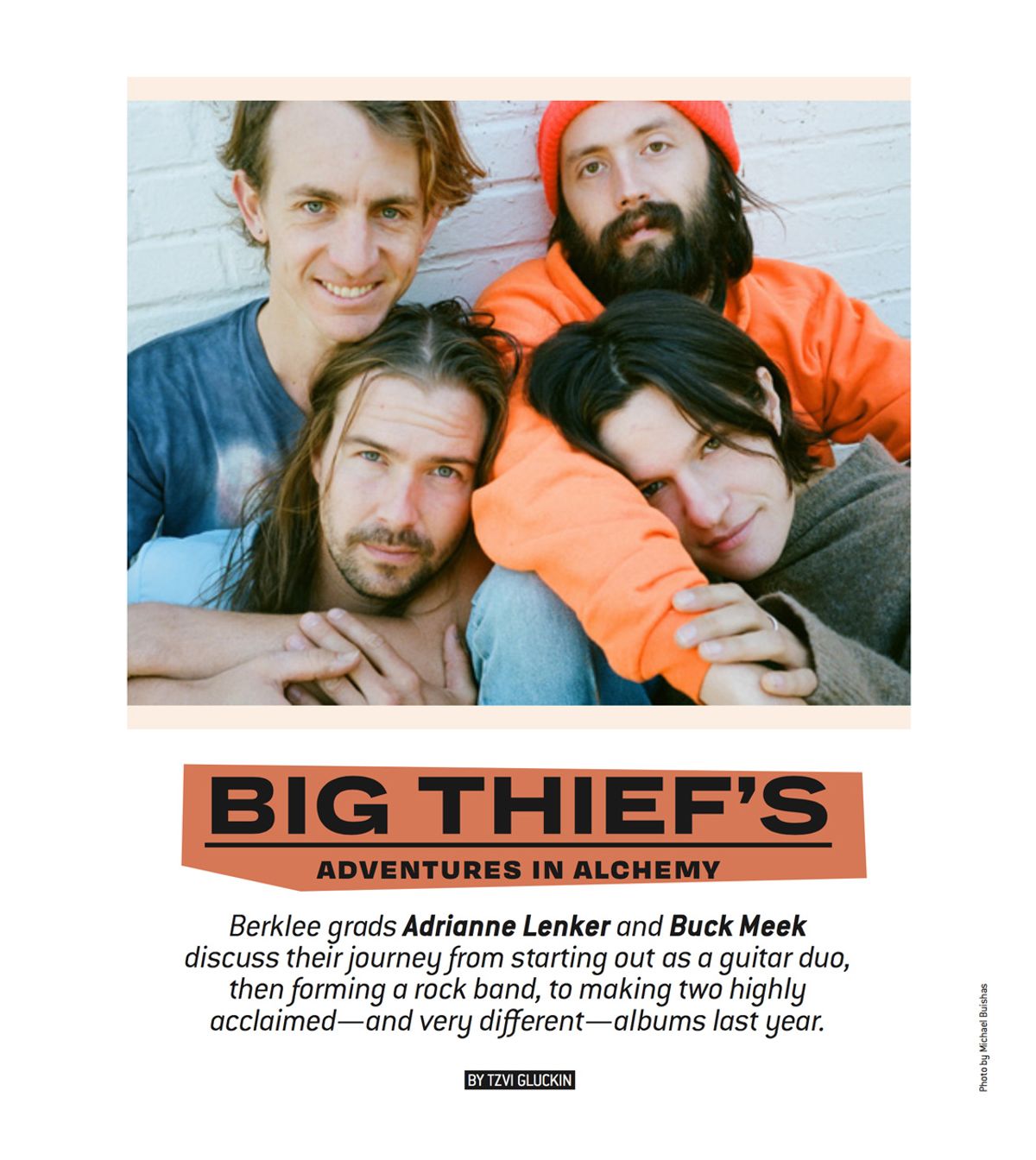

Berklee grads Adrianne Lenker and Buck Meek discuss their journey from starting out as a guitar duo, then forming a rock band, to making two highly acclaimed—and very different—albums last year.

According to Adrianne Lenker, the principle songwriter, lead vocalist, and guitarist for the New York-based indie band, Big Thief, sometimes it’s important to sound bad.

“What excites me the most is making my own road map on the guitar,” she tells us in our interview below, which was conducted on the phone from Europe while the band was still touring, before the world shut down due to the coronavirus pandemic. “Part of that process is sounding horrible, or just being able to playfully sound like crap … and not be afraid that I’m going to be kicked out of the cool club.”

That sense of adventure and daredevil curiosity is the band’s animating spirit. About a year-and-a-half ago, following its exceptional first two albums, Masterpiece and Capacity, Big Thief returned to the studio for the back-to-back sessions that resulted in last year’s very different releases, U.F.O.F. and Two Hands. First they went to Bear Creek Studio in lush, green, Washington state, and that expansive energy—by way of ambient soundscapes incorporated into their otherwise tight arrangements—permeates U.F.O.F., the album they recorded there.

“Our drummer, James Krivchenia, brought in what he called the magic box, which was essentially a pedalboard with some wild synths and modulation effects,” explains Buck Meek, the band’s other guitarist and backing vocalist. “He pulled a channel from the board in the control room through his magic box, and throughout the entire session, whenever he wasn’t playing drums, he was on the couch with that thing. At the end of the session, we had this huge bank of wild sounds that he had modulated from dry source material from the sessions, and we used that in the mixing process to create a lot of the ambiance that you hear.”

Big Thief made two albums with two different approaches in 2019. U.F.O.F. was recorded in Washington at Bear Creek Studio, with an experimental, ambient approach. Conversely, the stripped-down Two Hands was recorded live at Sonic Ranch in Tornillo, Texas.

A week after wrapping up at Bear Creek, Big Thief took up residency in the heat, at Sonic Ranch in Tornillo, Texas, near the Mexican border. There, they recorded Two Hands, their stripped-down masterpiece, which serves as a yin to its predecessor’s yang. Unlike U.F.O.F., Two Hands was recorded live, and highlights the band’s interplay and cohesiveness. Both albums, especially songs like “Contact” and “Not,” showcase their use of dynamics, the multiple textures they coax from their gear—often just by how hard they touch the strings—and the effort they expend crafting arrangements as a band.

That inquisitiveness applies to their gear as well. After a year experimenting and searching, Meek, along with Andrew Latham from Shure Microphones, prototyped the Whizzer, which is the white box you’ll notice sitting on top of his and Lenker’s amps. It’s also the focus of juicy gossip and debate on multiple gear forums. The device was inspired by Neil Young’s Whizzer, which is a mechanical knob turner attached to the top of his vintage Fender Tweed Deluxe. (Meek explains its development and how it works in our interview that follows.)

We spoke separately with Lenker and Meek about their different philosophies and approaches to music, songwriting, recording, and gear, and got a rare glimpse into the band’s fascinating process, and propensity to experiment.

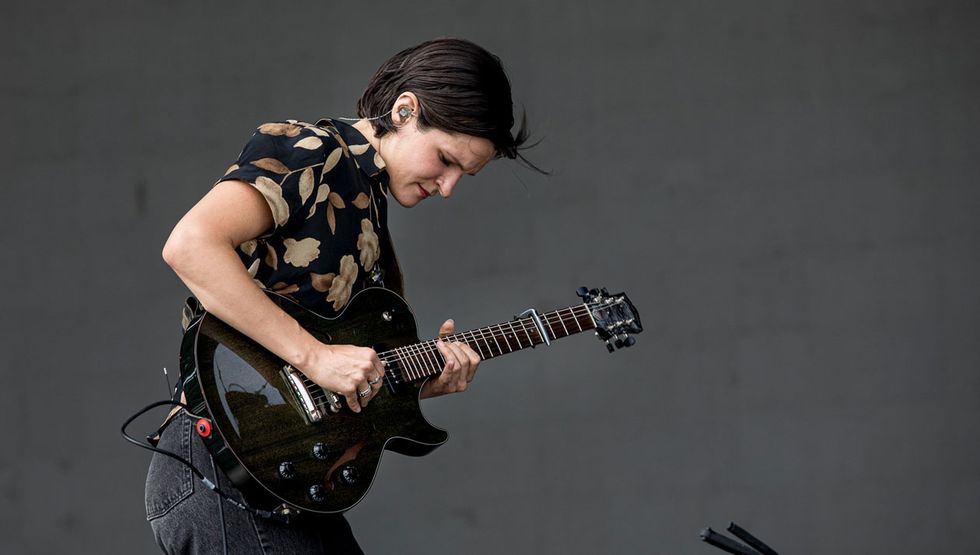

Adrianne Lenker uses a thumbpick and her nails to fingerpick her Collings SoCo, sometimes wearing buffed acrylics while touring. “I’m trying to learn how to be adaptable and play with the fleshy part of my fingers if I have to.” Photo by Tim Bugbee

ADRIANNE LENKER: “The word that we use for music is not presenting—it’s playing. We’re playing this music.”

Adrianne Lenker hails from Minneapolis and studied at the Berklee College of Music in Boston after winning a full scholarship. (The funds were thanks to guitar phenom Susan Tedeschi, who played a series of benefit concerts to create this scholarship). After graduation, Lenker moved to New York City and teamed up with her bandmate, Buck Meek. She spoke with us about her experiences learning guitar and finding her voice at a very early age, her preference for open tunings and capos, and why she encourages other songwriters to play her guitars.

You have a degree from Berklee, which has a very jazz-centric curriculum. What was your focus there?

I was a pro music major—that’s what they call it. It was performance-focused, but then it’s also a smattering of other interests. That was just one form of schooling that I got. When I was a teenager, I got another form of schooling, but I’ve always been focused on music. There was a lot of jazz in the curriculum at Berklee, but there were other things, too. It took me about a year-and-a-half or two years to find teachers who got what I was trying to do. But it was definitely heavily jazz-focused. I picked out the things that I resonated with, like spread voicings, inversions, and open voicings—certain voicings on the guitar that I felt were beautiful and that I could immediately apply to my songwriting—spread triad inversions and things like that, and then shed the rest of it.

In addition to creative voicings, do you use other tunings, too?

I’ve always done that. I started playing in tunings that I learned from books, like open D (D–A–D–F#–A–D), and also this Michael Hedges tuning, because I was really into Michael Hedges.

What was that?

C–G–D–G–G–G, with all of the high strings tuned to G. I started out learning tunings, but over time I tweaked the strings according to the notes I wanted to drone over the songs. I stumbled upon tunings by turning the tuning heads, experimenting, and exploring. More than half my songs are in open tunings.

Do you tune your guitar between most songs during your live set?

It’s very helpful that now we have someone tech-ing for us and helping with all the tunings, whereas before, our live sets would be limited. I would structure the sets around tunings.

Is that why you use the capo, too?

I love the capo. I always hear people joking about it, especially at Berklee. It was the “Steel Rod of Dependency”—that’s the joke—but it’s not true. Capos make it so you can have certain timbres. I’m drawn toward that ringing sound of the open strings, instead of just doing closed voicings for everything. I could figure those out if I wanted to, but I prefer the sound of the open strings.

Did you start out as an acoustic player?

I played acoustic from when I was 6 years old until I was about 22. I got my first electric when I was playing as a duo with Buck, right before the band started. I was serving in a restaurant full-time, and I saved up and got my first electric. I saved some more and bought an amp, and that was my first time really playing electric. I’d tried when I was a kid, but it didn’t resonate with me. I loved the vibrations with the acoustic guitar. I like physically feeling it on my body. I grew up playing fingerstyle and fingerpicking.

Is that still how you play now?

Yeah, and I use my nails, although recently I’ve been trying to challenge myself to not be so dependent on them. On the last few tours, I got three acrylic nails on my right hand, and I just kept them filed and buffed. I always played with my nails, but I had a guitar teacher at Berklee named Abby Zocher, and through learning with Abby, she taught me about refining the way to care for your nails. Abby played a lot of classical guitar. She showed me how to buff my nails properly. You don’t just use a nail file. You actually go around the bottom edge, and use all the different grades of buffing, and buff them until they’re so smooth that they can’t even get a nick in them. That’s the most ideal.

But with Big Thief, I end up playing a lot of rock ’n’ roll, and we get heavier in the songs. I go into my subconscious zone, and I break nails wailing on my guitar. The last few tours, I started to get acrylics on my right hand—the gels—because they’re strong, and filing and buffing them down until they’re smooth. But the problem with that is when you get them, they have to tear your real nail up and thin your nail out a lot, and it’s really hard on your actual fingernails. On this tour, I’ve been trying to stick it out. I’ve broken nails already and I’m trying to learn how to be totally adaptable, and not be too hung up on having a pristine sound. I’m trying to learn how to be adaptable and play with the fleshy part of my fingers if I have to.

Was Abby a big influence?

She honestly was the reason I stayed at Berklee. She saw me for me, and just got it. She encouraged me so much. I was one of very few girls in the guitar department—I recollect there were three other girls who were studying guitar. There was this one very specific way of teaching that a lot of the teachers had, and a lot of the kids were practicing shredding in this very specific way and trying to become the best possible shredder. You’d get ratings as a guitar player, “You’re a ‘seven,’ or a ‘five,’ or whatever.” Abby’s teaching was so much deeper. She was so good at seeing the strength in the individual students and helped them to become more and more excited about music.

What did she focus on with you?

I learn in a specific way. I learn through feeling it under my hands, and through immediate utilization of the chords or the scales or anything I’m learning. I learn so much better through making it immediately contextualized, or immediately incorporating it into something that’s inspiring. We would play and use whatever I was focusing on, use it in the most musical way possible. She didn’t get bent out of shape about, say, nailing this scale right now. It wasn’t about the books. When I was with her, I felt that it was about me, and my practice, and what I cared about. We would learn songs—I would show her stuff I was writing—and she would say things like, “This one chord you go to here, have you tried this other inversion?” Beyond that, her office was always open to come and talk, or cry, or whatever needed to be done [laughs].

Your style is very dynamic, but you seem to control that more with your fingers than pedals or even tweaking the knobs on your guitar.

It changes. It depends on the room, but I generally like to keep my amp pretty loud and use my knobs and my hands for dynamics. There are some parts that need to be extremely quiet. I learned a lot about dynamics through acoustic guitar, because you have to. If you’re not plugged into anything, all the dynamics are coming through your hands. I like the feeling that I can play clean or quiet, but then make it break up if I choose to dig in.

Guitars

Collings SoCo

Martin cutaway acoustic

1971 Martin 12-string dreadnought

Amalio Burguet nylon-string

Amps

Magnatone Twilighter 1x12

1956 Fender Deluxe tweed

Effects

“Whizzer” control footswitch with four gain stages

Analog Man Prince of Tone overdrive

Strymon El Capistan dTape Echo

Strings and Picks

D’Addario NYXL strings (.011–.049)

Plastic thumbpick

Do you do most of the songwriting, bring the pieces into the band, and then jam?

Everyone writes their own parts, but yeah, I write the songs. More and more, as we get closer and closer, we’re starting to play parts together in a way where we come up with something together. I write the lyrics, but Buck and I have cowritten in the past. We cowrote, “Replaced,” that song on Two Hands, and we’re starting to do more cowriting together. Buck and I frequently bounce ideas off of each other for our songs, but more and more we’re starting to write together. The band is starting to make song forms together, too. But primarily, I’m always working on song ideas. I’ll either have a finished song that I’ll bring, or I’ll have something that’s in pieces and we piece it together, together.

Do you keep it loose? When you’re playing live, will the songs change and take on a new life?

Definitely. The more relaxed and practiced we get, the more we improvise, change things, and try things. We’re always trying to push ourselves to try things that are scary. I also feel that it’s really important to sound bad sometimes.

How so?

I think there’s so much emphasis on performing as a presentation of something that’s polished or perfect or realized. I like the idea of experimenting with the idea of performing something that isn’t perfect or even realized, but maybe is just in its infant stages. Instead of performing for someone, as in, “Look at this great amazing thing.” It’s more like, “Look at this thing with blemishes and imperfections”—which we all have—and having permission to be in a process rather than to be totally put together. I also feel that with guitar, too. I look at it as a lifelong journey. Guitar is my number one passion, in a way, even before songwriting. It’s always been the vessel or instrument through which I’ve been able to connect most deeply with myself. It’s exciting to me, because I feel I can spend the next 60 years practicing guitar until I die, and not ever learn all there is to know.

There was a time when I was in Berklee, where I was freaked out about not being a good guitar player. There was a moment where a couple of teachers, or a couple of comments that I received, made me feel defeated. Some teachers said to me, “You don’t know what drop 2 voicings are? You’re not a guitar player.” Just straight up. But I feel it’s like any art form, like painting, there’s no right way to do it. There are all kinds of tools and vocabulary to learn, but ultimately what excites me the most is making my own road map on the guitar. Part of that process is sounding horrible, or just being able to playfully sound like crap. To even walk into an area that I have no familiarity with, and not be afraid that I’m going to be kicked out of the cool club. To be able to play all the wrong notes intentionally, to play things that are not profound, or not intricate, or not interesting—and not let that voice of self-doubt creep in, but just celebrate the beauty of the relationship with the instrument, and to truly try and find the playfulness in it. After all, it is playing. The word that we use for music is not presenting—it’s playing. We’re playing this music.

Just like real life, warts and all.

Yeah, and it’s way more fun that way. I did this solo recently and I shocked myself. When I hit, “wrong notes,” I’ve been doing this practice where I push into them more. It feels like there is no such thing as a wrong note. It’s just a matter of how you’re reacting to it. I was playing this thing that was completely out, and instead of panicking, and feeling like I’m failing, I just play, like, “Can I do that more? Can I play an even weirder or worse-sounding thing?”

U.F.O.F. and Two Hands were recorded very differently, but were there commonalities as well, in terms of gear, or how you set up in the studio?

How we did things varied. We were lucky enough to work with Dom Monks, who’s an incredible engineer, and also Andrew Sarlo, our producer, who did the last four albums. Their focus, for a lot of the recordings, was things like where we placed these things in the room, how we miked them, and how we best captured what was actually happening. In some cases, we’d put an amp in an iso booth or just block it off with sound barriers. In general, with U.F.O.F. things were a bit more isolated, because the nature of that record was trying to leave space for building soundscapes and textures. Whereas with Two Hands, we were all in the same room, and nothing was isolated. Max’s bass amp may have been just behind him, behind a glass door, but the drums, my amp, Buck’s amps, the vocals—we were all in the same room.

Could you touch or tweak your amps while you were playing if need be?

Yeah. That was the focus of that session. We wanted to capture that real feeling of simply playing together in a room, without too much added at all. The art form shifted there. Instead of leaving space, it was more about finding the fullness of the sound. Sometimes it would be as simple or nuanced as moving an amplifier two feet or moving a drum mic five inches. But that’s Dom’s area of expertise. We were focused on playing and Dom and Sarlo were doing their job, moving mics around.

Are you particular about gear?

Yes, but I just want to be able to use the thing in a very utilitarian way, to communicate the energy that I want to communicate. I think I can do it with anything. I like playing other guitars, too. I’m not afraid of going to a bar, or playing a house concert, or playing at a venue with some random person’s fucked-up guitar. I feel I can play a whole show that way and dig into it and feel good. But at the same time, I feel very specific in what my ideals are in instruments. I believe that instruments have spirits and they take the energy that’s put into them. I’m a big fan of passing a guitar around as much as possible and having as many people play it.

Because their energy gets into the guitar?

Yeah, and especially with certain songwriters. I’m like, “Here, do you want to take this and play it for a week or two?” I don’t always know what it is I’m going for. It’s always by feel. I like messing around and experimenting with things, but it’s usually beside the point. I don’t often have in my head that I really want a specific piece of gear. I just want to try stuff, turn knobs, hear things, feel the texture, see what it sounds like, and take it or leave it. And oftentimes I leave it, because my setup is pretty simple—just an amp and guitars at this point. I’ve gotten more simplified, I feel.

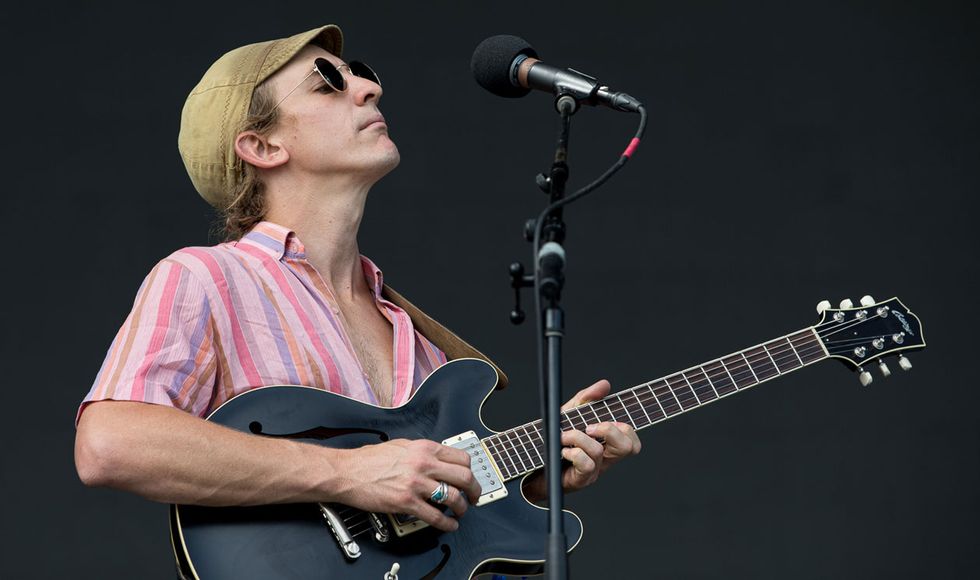

Buck Meek uses a hybrid style to coax different sounds out of his Collings I-30 prototype. “I do float my right hand, but I’ll also root my palm on the electric guitar quite a bit as well,” he explains. “I’m constantly shifting between a flatpick, storing my pick in my finger to fingerpick, and strumming with my thumb, even within one song.” Photo by Tim Bugbee

BUCK MEEK: “It’s more about an alchemy with my hands and the gear.”

Buck Meek grew up in Houston, Texas. He also has a degree from Berklee, but he and Adrianne Lenker didn’t meet until 2012, after they had both moved to New York City. Here, he explains how his years studying manouche-style acoustic informs his electric playing, his work on the Whizzer and how that changed his approach to pedals, and why he plays almost everything—including slide—in standard tuning.

You and Adrianne played as a duo before Big Thief started. How long did that last?

That was for a couple of years. That’s where it all started. We met in New York in 2012, and we started playing as a duo and touring. We bought an old Chevy conversion van and toured around the country a few times, just as the duo, and put out a record in 2014.

And that evolved into Big Thief?

Yeah, that evolved into Big Thief. That’s where we started to write our interlocking guitar parts. At that point she was playing acoustic and I was playing a Telecaster. We were writing songs together, developing our harmonies, and trying to write these woven guitar parts. Then she got an electric guitar from our friend, Aaron Huff, at Collings Guitars, and immediately started writing these rock ’n’ roll songs, like “Real Love” and “Masterpiece,” and it just became obvious that we needed a band. We built the band in 2014, which then became Big Thief.

You’ve been using Collings guitars for a while now.

We’re super lucky. I’ve been going to the Kerrville Folk Festival since I was about 13. I met Aaron Huff, who’s now one of my best friends, there, and he’s been going to Kerrville since he was a baby. It turns out that he’s in charge of the electric department at Collings. We became really close at the folk festival, and then, as Big Thief developed, he helped us fortify our rig with some Collings guitars. I have an I-35 with ThroBak humbuckers, and that’s my main guitar in Big Thief. I begged Aaron to prototype a fully hollow 330-style guitar. I think me and Anthony da Costa—who is a great guitar player—had both been begging him separately to prototype the fully hollow, which eventually became the I-30. I was lucky enough to get the prototype, and I play the prototype I-30. It’s pretty exciting. I also have a guitar on the bench right now from Flip Scipio. He’s building me his own version of a Strat, with a Guyatone pickup and a Fralin, and I’m super excited for it. I played one of my friend’s Flip Scipio guitars recently and it totally blew my mind.

But you’ve spent a lot of time on acoustic guitar, too?

I started playing my mom’s old Yamaha acoustic guitar. She gave me my first guitar lesson when I was 6 years old. She showed me the basic chords and taught me a couple of songs that she’d written back in the ’70s. We had a [Mohammed] Rafi VHS, the live concert, and I would play along to that every single day. When I was 8, my parents bought me a Strat, at Rockin’ Robin Guitars in Houston. I started taking electric guitar lessons at Rockin’ Robin. When I was in high school, a guitar player named Django Porter came in to teach at this charter arts high school I was a part of. He was this incredible manouche-jazz player, like Django Reinhardt, and I became his protégé. He took me under his wing and taught me to play that rhythm—like La Pompe-style rhythm, that French jazz rhythm. He plugged me into all these amazing players in the Texas Hill Country who were part of the Western swing scene, like some of the guys from Bob Wills’ old band and fellows like Slim Richey. I went full force into acoustic guitar in high school, and all through college at Berklee as well. I think that’s when I really learned how to find sounds with my hands versus pedals, which served me well when I then transitioned back into electric guitar.

I moved to New York after I finished college, and when I met Adrianne, I started playing electric guitar again. But from playing acoustic, I’d developed a real sense of how to coax sound out of the instrument just with my hands. Watching guys like Slim Richey, who’s this old jazz player, he would get a type of slapback delay sound out of his acoustic guitar, just with his pick. The whole technique for the manouche stuff—which I think Django Reinhardt essentially invented—was that he had his floating right hand. His picking hand never rested on the top of the guitar. It was just floating in the air, like with this kind of loose wrist, and I think that lets the top of the guitar resonate much more than anchoring your palm on the face of the guitar. It gives it an almost natural reverb or this kind of resonance. When Django played melodies, there was a lot of muting the strings with his left hand by releasing pressure. It’s almost like achieving the sound of a compressor. A really good manouche guitar player can almost create the sound of reverb somehow, too. It’s emulating these things that effects processors can produce, but just with the hand. That’s where I was coming from on the acoustic guitar. When I went to the electric world, I brought that with me. I’m always trying to do as much as I can with my hands. I recognize the importance of my gear, but I try to find equipment that steps out of my way, and that produces organic, rich sounds. But for me, it’s more about an alchemy with my hands and the gear.

Guitars

Collings I-3

Collings I-30

Bayard Guitars L-00 14-fret acoustic

1926 Martin 0-18K Koa

Amps

Magnatone Twilighter 1x12

Effects

“Whizzer” control footswitch with four gain stages

Ernie Ball volume pedal with JHS no-loss mod

Analog Man Sun Face fuzz

JHS Colour Box (for Neve board direct fuzz)

Walrus Audio Julia Chorus/Vibrato

Hologram Electronics Infinite Jets Resynthesizer

Red Panda Particle granular delay

Death By Audio Reverberation Machine

EarthQuaker Avalanche Run (for tape reverse)

Analog Man Sun Face fuzz

Strymon El Capistan dTape Echo

Strymon Zuma and Ojai power supplies

Strings and Picks

D’Addario NYXL strings (.011–.049)

Curt Mangan Monel strings for acoustic (.011–.048)

Dunlop JD Jazztone 207 picks

Do you use those techniques, floating the right hand and damping with both your right and left hands?

I’ve developed a hybrid style. With the electric guitar, in some instances, I do float my right hand, but I’ll also root my palm on the electric guitar quite a bit as well. I’m constantly shifting between a flatpick, storing my pick in my finger to fingerpick, or strumming with my thumb, even within one song. I’ll switch a lot of different right-hand techniques to get different sounds and different resonances.

Instead of pedals, you get your dynamics from your hands?

It’s all from our hands and from our amps. We had this fellow in Chicago prototype a device based on Neil Young’s Whizzer for us. Neil has this device that his guitar tech and electrical engineer built for him. It’s an actual robot that sits on top of his old tweed. It turns the knobs for him with these robotic servos, and therefore boosts the actual amp for his solos. I put out this request online to see if anyone could prototype something like that for us, and I found this dude in Chicago who works for Shure Microphones. He spent a year prototyping it for our Magnatone Twilighters, and he came up with this beautiful device that essentially bypasses the volume pot in the circuit with a TRS cable. There’s an auxiliary box with two robotic pots for volume and for master, and a footswitch that turns those robotic knobs to your presets. Essentially, it’s just a hand turning the knobs up and down for you.

That’s that white box on top of the amp?

Exactly. That white box is just an auxiliary volume knob that has a robotic pot that I can set with a footswitch, but essentially it’s not adding anything to the signal other than just bypassing the pot. I have four buttons on the floor and I have it set so that one is the amp at 4. The second footswitch is the same volume but with the gain—as if the amp is at 10—but with the master down so it’s equal volume to the clean sound. The third setting is a boost of that, which I can use as a boost or if I switch to a guitar with a lower output like a single-coil guitar, I can use that to bring my volume up to the same level. Then the fourth setting is full dimed, so the amp on 10. It’s so nice because it’s like having a third arm to turn the knobs, and to my ears, it sounds so much better to have the amp actually pushed versus an overdrive pedal. No overdrive pedal can give me that dirt sound that an amp can.

Did you have the Whizzers with you in the studio?

We had it starting at Bear Creek and Sonic Ranch for the U.F.O.F. and Two Hands sessions. Adrianne is playing the guitar solo at the end of “Not,” and that’s her Whizzer going up to 10.

How about at the end of “Contact”—same thing?

Yeah, for sure. We owe Neil Young a humble thank you for setting us off on this idea.

Adrianne uses a lot of alternate tunings. Do you use them as well?

I’m just in standard. I’m excited to dive into open tunings eventually, but I’ve always played in standard. When I was at Berklee, I found a great professor named David Tronzo, who’s a slide-guitar player. His whole philosophy is to play slide guitar in standard tuning. So even with slide, I always play in standard. I mute the unused strings with my right hand.

That must help distinguish your parts.

Yeah, for sure. That’s part of the interlocking that we’ve developed. At least half of our songs seem to be written in open tuning. A lot of Adrianne’s tunings are in lower registers, some of them are even almost in baritone registers, so there’s this natural spread of register between us a lot of the time, too, which is nice.

The different pickups and instruments must help you distinguish your tones sonically as well?

It’s mostly in the hands. For me, the gear is more to stay out of our way. We try to use equipment that stays in tune, and these Collings guitars are such good machines, they step out of your way. But beyond that, it’s all in your hands.

Do you experiment with different gear when you’re in the studio?

I experiment more with amps. On Two Hands, I’m playing a Fender Champ for almost the entire record. The session was mostly live in one room and the Magnatones were just too loud for how compact the session was. I switched to a little tiny Champ—an old ’50s Champ—and just cranked it up all the way. It was still quiet enough to have in the room without bleeding too much in the vocal mic.

Do you experiment with other guitars, too?

The first couple of days I always go crazy and pull every guitar out of the case, but I generally end up just going back to my Collings.

Dig Adrianne Lenker’s killer solo and the edgy dissonance she incorporates in this righteous live version of “Not” from Big Thief’s Two Hands album.